It can be easy to relate to the Enneagram solely as a personality system that describes various clusters of psychological type. Many of us are so blown away by the accuracy, richness, and depth that the Enneagram transmits that when we land on our dominant type, we spend most of our energy and effort there.

One of the gifts of the Enneagram Is that there is always more to be discovered, always an opportunity to open up new territory and insight. This investigation can include a robust study of how our dominant type works and can also expand beyond that.

This post is a journey into expansion, an inquiry into the place where Love and Attunement — two of the Essential qualities of Type Two (and the Two in all of us) — meet the Social Instinct, a drive to regulate our bodies through relating, belonging, and sensing our place within the wide web of humanity.

It also begins to dive into how emerging scientific knowledge appears to affirm what we’ve known through the Enneagram — that the way our bodies have evolved has created an amazing, adaptive vessel for receiving and responding to wisdom through the three centers of intelligence: body, heart, and mind.

Attunement Matters for Babies

Attunement is the basic language of social animals. Scientists and psychologists have known for years that babies need to experience feeling seen and resonated with to support healthy psychological and physiological growth. We experience the heartful, exquisite attention of Attunement as Love, another Essential quality of Type Two.

Why is Attunement so important for human animals in particular? Unlike many mammals, who can walk and perform basic functions soon after birth, human infants have nervous systems that are in need of a great deal of development after they are born. Human infants arrive in this world in a raw Essential state, unable to meet any of their survival needs and incapable of being consciously aware of themselves. When caregivers attune to their infants, they are carefully watching for and listening to primitive signals about their needs for nourishment, stimulation, and soothing. Over time, this kind of attention supports the development of a nervous system that can:

- Become consciously aware of its own needs for growth and regulation, and attend to them or ask others for help with what is needed

- Be more sensitive to the way our needs manifest within our specific organism, and how this informs what wants to be explored and expressed through us

- Sense how we are connected to others, and move in ways that honor this connection

The Healthy Two in all of us is primed to be attuned to how human needs are intelligent calls for nourishment, and to know that Love exists and is available to flow in a similar way to how we were spontaneously nourished through the umbilical cord in the womb. The Social Instinct in all of us has a drive for intelligent movement based in the sensation of our connection with others.

Attunement Matters at Any Age

Attunement is critical not only for the developing nervous systems of babies and children, but also for regulating the human nervous system at any age. Why is having a well-regulated nervous system so important? When our nervous system is healthy and well-regulated, our bodies are able to respond appropriately to what is needed in any given situation. A healthy nervous system constitutes a foundation for the basic survival of our physical bodies, and it allows us the possibility of moving beyond mere physical survival and into thriving in relationship with ourselves and others.

One of the capacities of a healthy nervous system involves a process called neuroception. Neuroception, which happens far below the level of conscious thought, describes how our bodies assess risk by processing social and environmental cues. When people are raised with attuned caregivers, they have the instinctive ability to interpret facial expressions and voices and can correctly assess whether another person is safe or dangerous. Lack of attunement in childhood, which includes childhood abuse or trauma, interferes with neuroceptive capabilities. People with a history of abuse or trauma can easily misinterpret social and environmental signals, and feel threatened by or unsafe with those who are exhibiting benign or positive expressions and vocalizations, while also failing to recognize danger signals when they are present.

When neuroception tells us that we are safe, the body is free to direct its resources to maintain a dynamic homeostasis that promotes physical growth and restoration. Heart rate is lower, the immune system is stimulated, and the sympathetic nervous system — the part that gears up to “fight/flee/freeze” in response to stress and threats — is inhibited.

When we’re in this place of having a regulated and calm nervous system, we have a stable and dynamic platform from which to consciously nurture higher levels of development. We have the energy and the presence to:

- Observe ourselves, so that we can see what we’re really up to. When we see ourselves clearly, we have the opportunity for choice and change. It is impossible to work with physical, emotional, or mental patterns that are operating outside of our conscious awareness.

- Practice new ways of being in our bodies, to develop more capacity and resilience

- Have compassion for ourselves and others. We can engage from a place of honoring each other’s autonomy and gifts, thus providing the space for genuine collaboration and mutually-beneficial partnerships

When we are contemplating what it takes to move out of the habitual tendencies of our Enneagram personality traits and to be in a state of presence that allows Essential wisdom to flow, this is a big part of what we’re talking about. We need a basic receptivity and availability in our bodies to develop a vessel that can hold a more mature Essential self. A body that feels under threat uses its resources to defend itself and cannot allocate resources toward cultivating a different level of awareness.

Special Sensor for Attunement and Social Engagement in Mammals: The Vagus Nerve

You are probably familiar with the concept of how animals employ strategies of “fight, flight, or freeze” as a response to stress and danger. In the last 25 years, we’ve learned that there is another way that mammals have evolved to respond to stressful situations: through the social engagement system of speaking, listening, gazing, and facial expression.

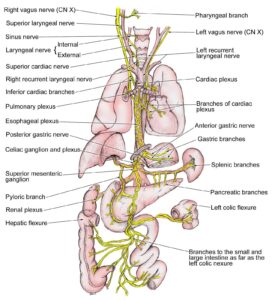

This social engagement system is mediated by the vagus nerve. “Vagus” means “wandering” in Latin, which is an apt name for the extensive way this nerve winds from the head through the neck and face, and then through the bronchi, heart, and gut (it’s the yellow thread in the diagram). The vagus nerve is the longest nerve in the body, and you might have noticed that it touches all three centers of intelligence. It’s a two-way highway for communication between the brain and other critical organs in the body, and an agent in the process of neuroception. When the vagus nerve is stimulated through the social engagement system, it facilitates a dynamic homeostasis in the body, and we feel a sense of well-being and connection with ourselves and others.

What else is special about the vagus nerve? This nerve has two branches: an older branch that human beings share with all vertebrates, and one that is a more recent evolutionary feature specific to mammals. The older branch (the unmyelinated vagus) touches the visceral organs below the diaphragm, including the gut, and reflexively regulates our internal organs. The newer branch of the vagus nerve (the myelinated vagus) has become integrated with the nerves that govern the movements of face and the neck, and is a highway for connection between social engagement movements in the face and neck, resonance in the heart, and regulation in the body.

In all animals, the newest evolutionary system is the one we turn to first when we find ourselves in stressful situations. Mammals under stress begin by turning to social engagement to regulate themselves and restore a sense of well-being. If that doesn’t work, or if the situation is more extreme, mammals move on to mobilization strategies (fight or flight), and if mobilization is not possible, to immobilization strategies (freeze or faint). Humans, like all social animals, are wired to try to connect as a first strategy when there is stress or disharmony.

When we are working with harmonizing the intelligence of the body, heart, and mind in our Enneagram studies, it can be useful to know that we’re not just talking about some theoretical construct of how human beings work. Just looking at the diagram of how the vagus nerve winds through all of the centers is a great visual reminder that each of the centers affects the others, and can enhance our motivation to continue to engage with the Fourth Way emphasis on the importance of working through all three centers simultaneously.

Interoception: A Way to Deeply Attune to Ourselves

If neuroception — the way that our body assesses risk — is an unconscious process affected by the experiences of our childhood, then what can we do to influence the way that we respond to the stresses and joys of life?

One way is through developing another innate capacity of human beings: interoception. Stephen Porges, the founder of Polyvagal Theory, speaks about interoception as a sixth sense. We use our traditional five senses to perceive data from the external world, but we also have the sixth sense of interoception as a way to take in information from our internal world, from our viscera. Porges says that interoception — the ability to sense and regulate our internal state — “is at the basis of human competencies in higher-order behavioral, psychological and social processes.“

Although interoception is such an important skill, many human beings get very little support or training in developing this sense. Even when we notice what’s happening inside us, we often don’t have the vocabulary to describe it, often using a vague notion of “what I feel” to try to capture the sensations of our bodies. Interoception is the basis of the healthy Self-Preservation Instinct, where we sense our internal bodily state and can respond appropriately. From this foundation of connection with ourselves, we can learn to extend from our body to other bodies via the Sexual and Social Instincts.

Porges also tells us that “the vagus, with its sensory and motor pathways, is the primary component of the interoceptive system.” Understanding how the vagus nerve is stimulated and toned is a portal to effective self-regulation of the physical body.

Practicing Self-Regulation and Attunement

Interoception is a critical capacity for the full development of the Essential self. Our bodies are a vast treasure chest of information about ourselves in connection with the world. The ability to attune to the language of the body on its own terms is how we learn to regulate ourselves and to attend to our physical and Essential needs.

Some ways that you can develop your interoceptive sense include:

- Body scans. Many spiritual traditions have practices of systematically sensing each part of your body to tune into what’s going on inside. Body scans help you to sharpen your ability to sense more of your organism, and to be with whatever information your body has for you without judgment.

- Inner Smile Meditation. These Taoist exercises focus on the connection between emotions and the body. They encompass a variety of ways to bring smiling and loving energy to the heart, lungs, kidneys, liver/gall bladder, and stomach/spleen.

- Breathing practices. Conscious breathing touches all the areas connected to the myelinated vagus — the lungs, heart, and the muscles of the face and neck. As a result, many breathing practices have a profound effect on vagal tone and interoceptive capacities. Two examples:

- Coherent Breathing. Breathing at a rate of 5-6 breaths per minute has been proven to synchronize the heart, lungs, and brain into a resonant rhythm that creates vagal health and a resilient nervous system.

- Integrative Breathwork. A potent and safe breathing practice that helps us learn to be with and say “yes” to everything about us, whether somatic, emotional, mental, or spiritual.

References

Most of the scientific information in this post comes from the work of Stephen Porges, Ph.D., the founder of Polyvagal Theory. If you’d like to geek out directly from the source, here are a few recommendations:

- This article is a good basic introduction to the theory: The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system

- More technical, scientific reading: The Polyvagal Theory by Stephen Porges, Ph.D.

- More approachable reading that will help you to understand the applications of this theory in a clinical setting: The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation by Deb Dana

black and white photography by Ilaria Chiantore